|

| International News Photo |

| Dixiecrats at the Alabama state convention in 1948. |

|

| Associated Press |

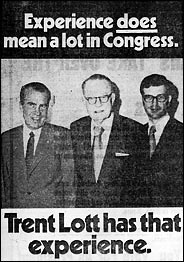

| An advertisement from Trent Lott's first congressional campaign in 1972. The man in the middle is William M. Colmer, a Mississippi segregationist whom Mr. Lott succeeded in Congress. |

WASHINGTON — Last week Trent Lott, the incoming Senate majority leader, learned the truth of William Faulkner's dictum, so often applied to the South: "The past is never dead. It's not even past."

But first, the nation needed a crash course in the rougher and more complicated parts of its own history. About the angry rise of the Dixiecrats in 1948. About the role that race played in the Republican realignment of the South. About Senator Strom Thurmond's long defense of segregation, and his final defection from the Democrats in 1964, after they pushed through the landmark civil rights bill opening public accommodations to blacks. About Mr. Lott's own history of opposing significant civil rights legislation.

What was striking was not that this past reared its troublesome head after Mr. Lott delivered his praise of Mr. Thurmond's 1948 presidential campaign as the nominee of the Dixiecrats, a "states' rights" party devoted to the preservation of a segregated South. What was striking was how long the reaction took to build, how distant the memories had become, how many politicians were initially caught off balance.

Americans often tend to sanitize their past, smooth the edges, develop a happy amnesia about the hardest parts, particularly when the subject is race. In the culture at large, the story of civil rights has become a simple morality tale of a great wrong righted by a just people through the intercession of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. But historians say the agonizing struggle and chaos of that era — when the ultimate outcome did not seem inevitable, when the best way to get there was not apparent and yet many people still had to make a stand — gets overlooked.

"What's fascinating about the Lott episode is it brings back the reality" that "people had to fight, some had to lose their lives, to win these rights," said Roderick Harrison, a sociologist at Howard University and an official with the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, a research group that focuses on issues facing black Americans. "That it was bitterly resisted. That Martin Luther King, who is now sanctified, was looked at as a dangerous radical."

The urge to tidy up the story is strong. Consider Mr. Thurmond, who was bid a sentimental farewell from the Senate this month as a kind of national grandpa, the long, morally ambivalent arc of his career turned into an uplifting narrative of a man who changed with the times. "Life is easier if there are no former segregationists around," said David J. Garrow, a civil rights historian.

Even Dr. King, who now looms as an immense figure in popular history, has been blurred, transformed into a smooth icon of racial brotherhood, rather than the more difficult figure who also challenged the political establishment on the Vietnam War and economic inequity.

Part of the blurring of that era is explained by simple demographics: more than half of all Americans alive today weren't even born in 1964; nearly 80 percent weren't born in 1948.

"I know where I was when I heard of King's assassination, Robert Kennedy's, Malcolm X's," Mr. Harrison said. "These kinds of things are indelible. It is quite different when you are seeing things as historical events."

Moreover, James W. Loewen, a sociologist at Catholic University, argues that such history is often taught "as a parade of dead facts," drained of its relevance, because "teaching the past with relevance to the present is intrinsically controversial." For example, he said, many high school history textbooks skirt the subject of how the modern Republican Party benefited in the South from the votes of defecting Democrats angry over civil rights.

There are, in fact, reasons for both parties to step lightly over this history. Before it adopted a civil rights plank in 1948, the Democratic Party was, for many years, the "white South's instrument for pursuing the goals of white supremacy," as Merle Black, a political scientist at Emory University, put it.

Against this backdrop, the furor over Mr. Lott ultimately became a national tutorial. Addressing a 100th birthday party for Mr. Thurmond on Dec. 5, Mr. Lott, a lifelong Mississippian, declared of his state: "When Strom Thurmond ran for president, we voted for him. We're proud of it. And if the rest of the country had followed our lead, we wouldn't have had all these problems over all these years, either."

Mr. Lott said he was simply trying to praise a retiring colleague on his birthday. He maintained that he had made a poor choice of words, but that it was a "mistake of the head — and not the heart." He insisted he was trying to honor Mr. Thurmond for his work on national defense and fiscal matters, not his defense of segregation. Republicans grumbled that the controversy was fanned by Democrats eager to wound an incoming majority leader after they had suffered big losses in the midterm election.

IT took time for the backlash to develop. As Alan Brinkley, a historian at Columbia University, put it, "you had to know something" about the Dixiecrats, who captured 92 percent of the white vote in Mississippi in 1948, to understand the provocative nature of Mr. Lott's remarks. It took five days for Senator Tom Daschle, the Democratic leader, to denounce his comments, and seven days for President Bush to do the same.

"Different Americans reacted differently," said Julian Bond, chairman of the N.A.A.C.P., and a professor at American University and the University of Virginia. "Black Americans were angry. White Americans were ashamed. And sometimes, shame makes you push the memory away." He added, "As a nation we're not comfortable with this memory."

Representative John Lewis, the Georgia Democrat who was on the front lines of the civil rights movement, agreed that Mr. Lott's casual endorsement of the Dixiecrats ultimately "touched a raw nerve." He was a child in Alabama during the 1948 campaign, but said he remembered it well.

"Strom Thurmond walked out of the convention in 1948, and the Dixiecrats met in Birmingham, Ala., where he was nominated. It was a period of tremendous fear on the part of African-Americans. There was just fear."

BY week's end, the new majority leader was fighting for his political life, apologizing again, with his political record on civil rights coming under intense scrutiny. "Let me be clear," Mr. Lott said Friday night. "In celebrating his life, I did not mean to suggest in any way that his views of over 50 years ago on segregation were justified or right. It was wrong and immoral then and it is now. By the time I came to know Strom Thurmond — some 40 years after he ran for president — he had long since renounced many of the views of the past, repugnant views he had had."

In fact, Jack Bass, Mr. Thurmond's biographer, said he found it interesting that when the monument to Mr. Thurmond went up on the statehouse grounds in Columbia, S.C., a few years ago, "it did not mention his '48 presidential campaign, and he approved the wording of it."